In part 3 of my “Beginners Guide to Training With Power” we'll look at building a few performance profiles. There are two key metrics that will determine where you focus your training time. Before you read on, I suggest you read the previous articles to refresh your memory as to what we're talking about:

Beginner's Guide to Training with Power: Part 1

Beginner's Guide to Training with Power: Part 2

Once you've refreshed your memory, we'll focus on two topics that will heavily govern your training and racing strategy. These are your power and fatigue resistance profiles.

I'll describe each of them after the break and tell you how they can guide your training.

Training with power and fatigue profiles

These two metrics are keys to building your training plan and guiding your training and racing strategy. The first of these is your power profile. It will help you to identify strengths and weaknesses. It's a collection of several weeks or months of power data and is sort of like a pop quiz for your body. It will tell you what your strengths and weaknesses are: is your body good at sprinting or time trialing? It is also a key way to determine if you are putting too much time into one specific energy system and neglecting others. Finally, it can give you a clue as to your natural strengths and weaknesses.

The second key to identifying strengths and weaknesses if your fatigue resistance profile. A fatigue resistance profile helps you to determine what your “winning strategy” should be. Will you be the drag racing sprinter who goes from 300 meters out? Are you the guy who can blow the doors off a Ferrari in the last 50 meters? Do you solo in from the 5K to go climb? Should you save it for the Flamme Rouge? The fatigue resistance profile helps you tailor your strategy to your strengths.

Let's explore each profile individually.

Power Profile

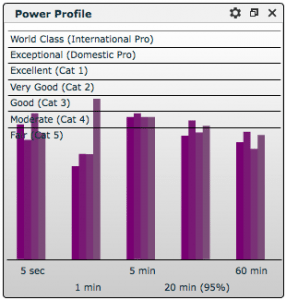

An athlete's power profile is a collective assessment of their historical power data. When graphed, it reveals their strengths and weaknesses on paper. It can tell you if you're stronger at longer or shorter efforts. It can alert you that you need to work on 5-minute efforts. It's perhaps one of the best ways to determine your primary training focus. While it is a very useful tool, it does take a fair amount of data collection to make it useful. That means you'll probably be training in the dark for a few weeks before you have your profile.

One of the things to note about the power profile is that you can set the interval duration to read anything from a couple days to a month. I usually set interval duration to 1 month (28 days) in order to get a good spread of data. It is spaced enough to show improvement or decline and lets the athlete focus on areas to improve. With that in mind, let's look at a sample plot and see where we should be spending training time.

In this example (from Trainingpeaks) we have the interval duration set to 28 days, so each bar represents 4 weeks of training data. In this case, you can see a variable effect for 5 second and 60-minute power. You can also see a plateau in 5-minute power, a gradual rise in 20-minute power and a sharp rise in 1-minute power.

In this example (from Trainingpeaks) we have the interval duration set to 28 days, so each bar represents 4 weeks of training data. In this case, you can see a variable effect for 5 second and 60-minute power. You can also see a plateau in 5-minute power, a gradual rise in 20-minute power and a sharp rise in 1-minute power.

From this data, we can make a few assumptions. The athlete in question probably performs well when making sharp attacks and riding them out for around 5 minutes. The athlete's biggest limitation is their functional threshold power. In this case, training should be focused primarily on raising FTP. The plateau in 5-minute power suggests that this is where the athlete's natural talent lies, and it would be easy for them to get stuck in that training zone often (since they excel at it.)

Overall, the athlete in question is reasonably well rounded, not specifically good at any one thing, and not terrible at anything either.

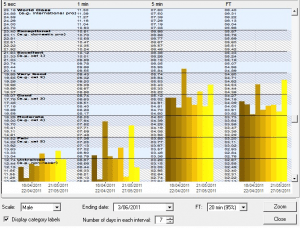

In this example (from WKO+) we see a very gradual rise in 5-minute power and functional threshold power. On the other end of the spectrum, we see that 5-second power is poor, and 1-minute power is all over the place. There's no readily apparent trend at all. At this point, it appears the athlete needs to adjust their training plans to improve on their 5 second and 1 minute power numbers. They could also focus on building in some functional threshold power intervals.

In this example (from WKO+) we see a very gradual rise in 5-minute power and functional threshold power. On the other end of the spectrum, we see that 5-second power is poor, and 1-minute power is all over the place. There's no readily apparent trend at all. At this point, it appears the athlete needs to adjust their training plans to improve on their 5 second and 1 minute power numbers. They could also focus on building in some functional threshold power intervals.

Typing this athlete, I would consider them as a TT specialist or a “diesel” climber. Working on 5 second to 3 minute power would help to make this athlete more well rounded. It would give them a better chance to win from a group as opposed to having to make a solo break for the win.

It's worth noting that the power profile is a tool that was developed by Andy Coggan and Hunter Allen for WKO+. It's also available on Trainingpeaks.com and on Golden Cheetah as well. I use Golden Cheetah for my own data and run most of my client data through it as well.

Fatigue Resistance

Fatigue Resistance

Taking the power profile a step further we arrive at fatigue resistance. This will be the key to planning your race strategies and to some extent your training schedule.

Imagine two sprinters are relatively evenly matched and they start training to try and beat each other. Sprinter A spends all his time training his sprint power, and raises his 5 second wattage to 1500 watts. Yet he never wins and sprinter B is always beating him. Sprinter A gets frustrated and keeps asking “Why?”

Here's an example of how.

Sprinter B only has a 1200 watt sprint. He also works his FTP and VO2 max zones. He can put out the power to be there in position at the end of the race to unleash that sprint. From reading his fatigue resistance profile he knows that he's not a drag race type sprinter. His acceleration is huge, but is not maintainable. Knowing that, he positions himself to zip around his rivals in the last 100 meter dash to the line.

Drilling down the data in your power profile will tell you not only what kind of rider you are. It also explains which way you excel in that category of rider. Are you a drag race sprinter or a fast dash to the line sprinter? Do you TT in from 5K out or attack at the flamme rouge? Are you able to spring out of the pack on a climb and maintain that gap all the way up or should you hang in and kick for the top in the last 250 meters?

Not only can the fatigue resistance profile tell you where you excel, it will point out the holes in your fitness. If an athlete has below average fatigue resistance from 10 to 20 seconds, they should work on those 20-second efforts. If there is a significant drop-off from 5 minutes to 8 minutes, longer VO2max intervals may be necessary.

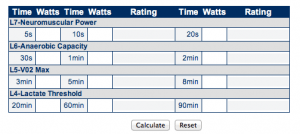

You can evaluate your fatigue resistance profile in my Zone 4/5/6/7 power test. You'll want to use your mean maximal values for each duration to get accurate data that reflects a refreshed athlete. You may want to test the Zone 4 and 5 on one day and zone 6 and 7 on another. The hazard of testing ALL your power points on one day is accumulated fatigue.

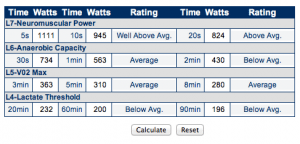

Let's look at another example. This time, we have an athlete who has tremendous endurance at high power outputs. They probably excel in a drag race to the line. They have slightly below average zone 6 fatigue resistance at 2 minutes. This suggests they have a hell of a kick but have a tough time maintaining it. If they are able to accelerate away from the pack, they are able to ride it out up to 8 minutes. Should that move go beyond 8 minutes and stretch into a long breakaway, they'll have a tough time making it stick.

Let's look at another example. This time, we have an athlete who has tremendous endurance at high power outputs. They probably excel in a drag race to the line. They have slightly below average zone 6 fatigue resistance at 2 minutes. This suggests they have a hell of a kick but have a tough time maintaining it. If they are able to accelerate away from the pack, they are able to ride it out up to 8 minutes. Should that move go beyond 8 minutes and stretch into a long breakaway, they'll have a tough time making it stick.

In essence, I'd recommend this athlete should work on their 1 to 2-minute efforts. Build the ability to maintain their short-term power output and then focus on FTP and longer intervals to maintain their output for the duration of group rides and races.

In our last installment, the Beginner's Guide to Power (Part 4) we'll discuss using your power data to train for specific events.