Unless you've been under a rock, you'll probably know that this past weekend has been a bad one for Specialized. Earlier this year, Specialized issued an ultimatum to the owner of a small Cochran (Alberta, Canada) bicycle shop by the name of Cafe Roubaix. Their letter stated that his shop is infringing on their trademark on the name "Roubaix." The claim is that common passers by would associate the name on the sign with Specialized and more specifically, the Roubaix model.

Unless you've been under a rock, you'll probably know that this past weekend has been a bad one for Specialized. Earlier this year, Specialized issued an ultimatum to the owner of a small Cochran (Alberta, Canada) bicycle shop by the name of Cafe Roubaix. Their letter stated that his shop is infringing on their trademark on the name "Roubaix." The claim is that common passers by would associate the name on the sign with Specialized and more specifically, the Roubaix model.

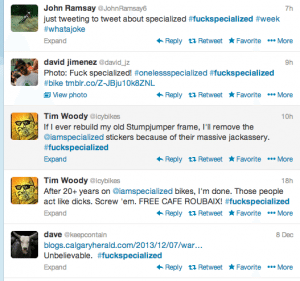

After this news broke, and with Specialized's history of playing the legal bully, the community sprang into action. Particularly the online community, who have been pointing out (in no uncertain terms) that they are disgusted with Specialized's legal tactics. But what is the story behind the Roubaix trademark and why is this making such a dramatic news story?

Click through for further discussion of why this may be the last straw for Specialized.

Specialized is claiming that Cafe Roubaix is infringing on their intellectual property (IP) by using the name "Roubaix" (if I understand IP law correctly, the "cafe" is disclaimed, so it has no bearing on the actual name of the shop.) But on the angle of market confusion and dilution, interestingly, Cafe Robaix does not produce anything except wheels (which are of course branded as Cafe Roubaix), but Specialized has determined that the very name is a threat to their intellectual property. In fact, the only response from Specialized has been when contacted by the Calgary Herald (who initially broke the story) and is as follows:

“A simple trademark search would have prevented this,” Koury wrote in an email, along with a reference to the federal government’s trademark database showing Specialized’s registration of the word Roubaix. “We are required to defend or lose our trademark registration.”

Now, I understand that IP protection is important, but there are a few issues with Specialized's trademark, as explained in this post by a Canadian IP attorney on SlowTwitch. (Important parts bolded.)

Apart from the spelling of the word "trade-mark" with a hyphen, Canadian and U.S. trade-mark law are largely similar. Canadian trade-mark law, though, places more emphasis on avoiding consumer confusion than protecting brand equity. In Canada, a registered trade-mark is valid only if it is "distinctive" – that is, a trade-mark is not valid if consumers can't readily tell whether or not two products using the same trade-mark are from the same company. The test for trade-mark infringement is the same – are people who buy a bike at Cafe Roubaix likely to believe that they are actually buying that comfy race bike that they read an ad for in Bicycling Magazine?

Where goods are closely related (for example bikes and bike parts) and the mark is exactly the same, there is a greater likelihood of confusion. But where goods are sold in different channels of trade and target different consumers, even identical trade-marks can co-exist without confusion (for example, in Canada, "Purolator" is a registered trade-mark of both an oil filter company and a separate courier company. For historical reasons, even their logos are identical but the mischief of confusion is pretty much non-existent).

Where the marks are not identical, for example "Roubaix" for a bicycle and "Cafe Roubaix" for a bike shop, the issue is whether the similarities in the marks and the wares are so strong that consumers are likely to be confused about who they are really dealing with when they go shopping (or at least misled into believing that there is some relationship between the two companies). As others have pointed out, lots of people in Canada sell products to cyclists that are marked with the word "Roubaix" – Roubaix cycling tights at MEC, Challenge Roubaix tires, etc.

Specialized finds itself in a tough place – it has registered the trade-mark "Roubaix" for bicycles but if they tried to come out with Roubaix branded jerseys or tires, they would probably get challenged because others have prior use of Roubaix for those types of products. The scope of distinctiveness for Specialized's trade-mark is, therefore, very narrow – it probably is not "distinctive" for anything other than bikes and perhaps frames or other components that Specialized may have sold marked with the Roubaix name. In fact, according to the Canadian Trade-marks Database, Specialized's registration applies to "Bicycles, bicycle frames, and bicycle components, namely bicycle handlebars, bicycle front fork, and bicycle tires." It strikes me that there may be multiple ways to attack the validity of the registration and/or whether there is really any infringement by the way that Cafe Roubaix is using the word.

From Cafe Roubaix's perspective, the legal fees might not be a problem – this is the kind of case that a lawyer might well be willing to take on pro bono. The problem is the cost of gathering the evidence of likelihood (or not) of confusion. Maybe this is the type of case where social media could be helpful in demonstrating that the relevant consumers in Canada know the difference between a small bike shop in Alberta and one of the sub-brands of a multinational bike manufacturer.

One solution that could be mutually beneficial under U.S. law and that a few people have mentioned, is probably not available in Canada. Under Canadian law, the use of a trade-mark by a licensee of the registered owner does not affect distinctiveness but only if the trade-mark owner exercises control over the character and quality of the goods that are sold in association with the trade-mark. Since Cafe Roubaix sells bikes and components from a number of companies that are competitors of Specialized, it is not possible for Specialized to exercise that control. Without that control, use of the mark, even by a licensee, destroys the distinctiveness that is an absolute requirement for the validity of the trade-mark.

There might still be some creative approaches that can make everyone happy. So far, though, it sure looks like one side has built a lot of good will and the other, well …

Let's take these items one by one:

In Canada, a registered trade-mark is valid only if it is "distinctive" – that is, a trade-mark is not valid if consumers can't readily tell whether or not two products using the same trade-mark are from the same company.

[pullquote]The estimated $150k in legal fees could be an issue….or could they?[/pullquote]In this case, many people are (probably correctly) stating that the Specialized Roubaix trademark is not valid because it's plainly obvious to the market segment who will be purchasing Cafe Roubaix products that these are not produced by Specialized bicycle corporation. Remember that Cafe Roubaix is a seller of boutique wheels and higher end merchandise. Those consumers are better educated than the average Wal-Mart bike shopper/consumer.

Where the marks are not identical, for example "Roubaix" for a bicycle and "Cafe Roubaix" for a bike shop, the issue is whether the similarities in the marks and the wares are so strong that consumers are likely to be confused about who they are really dealing with when they go shopping (or at least misled into believing that there is some relationship between the two companies). As others have pointed out, lots of people in Canada sell products to cyclists that are marked with the word "Roubaix" – Roubaix cycling tights at MEC, Challenge Roubaix tires, etc.

Again, to the point of similarity, it's plainly obvious that there's no similarity between the Roubaix bicycle and the Cafe Roubaix wheels.

…according to the Canadian Trade-marks Database, Specialized's registration applies to "Bicycles, bicycle frames, and bicycle components, namely bicycle handlebars, bicycle front fork, and bicycle tires." It strikes me that there may be multiple ways to attack the validity of the registration and/or whether there is really any infringement by the way that Cafe Roubaix is using the word.

What is, in essence, being said here is that there is enough difference in the usage of the word Roubaix that it may be possible to defeat the trademark registration through legal challenge. Of course, the estimated $150k in legal fees could be an issue….or could they?

From Cafe Roubaix's perspective, the legal fees might not be a problem – this is the kind of case that a lawyer might well be willing to take on pro bono. The problem is the cost of gathering the evidence of likelihood (or not) of confusion. Maybe this is the type of case where social media could be helpful in demonstrating that the relevant consumers in Canada know the difference between a small bike shop in Alberta and one of the sub-brands of a multinational bike manufacturer.

This is exactly what the Twitter and Facebook monsters are doing right now: they are hammering Specialized for their action, pointing out that there are such differences between these two entities that there should be no validity to the trademark. And believe me, Specialized is not faring well in the social media spotlight, with articles being written about the social media storm that's followed the original Calgary Herald article. It doesn't help that Specialized has no trademark claim in the US for the term Roubaix. In fact, THEY lease the name "Roubaix" from ASI, the group that owns Fuji, Kestrel, etc. According to Patrick Cunnane, president of ASI:

This is exactly what the Twitter and Facebook monsters are doing right now: they are hammering Specialized for their action, pointing out that there are such differences between these two entities that there should be no validity to the trademark. And believe me, Specialized is not faring well in the social media spotlight, with articles being written about the social media storm that's followed the original Calgary Herald article. It doesn't help that Specialized has no trademark claim in the US for the term Roubaix. In fact, THEY lease the name "Roubaix" from ASI, the group that owns Fuji, Kestrel, etc. According to Patrick Cunnane, president of ASI:

"ASI owns the Roubaix trademark in the USA," Cunnane said. "ASI purchased the Fuji and Roubaix (and many other) trademarks from the Japanese owners of the Fuji brand when ASI was formed to purchase the company in 1998. Fuji uses the Roubaix mark worldwide and has since 1987. ASI licenses the trademark to Specialized."

Finally, this whole media circus probably wouldn't have happened had this not been a pattern with Specialized. If you recall the Epic Wheelworks lawsuit, the Volagi lawsuit and the Mountain Cycles "Stumptown" debacle, you'll know that Specialized is no stranger to the legal process and is quite at home in a courtroom. However, this history of "bad behavior" on the part of Specialized seems to have finally hit the breaking point, with people having had enough of the litigious giant picking on smaller businesses. To say the least, the community has poured on the pressure, and (as of writing) there's been no response from Specialized on the issue.

However, there may be a happy ending in the cards yet.

ASI (the same company that licensed the Roubaix trademark to Specialized in 2003) has released a press release as of today 12/10/13 stating the following:

ASI says it owns the worldwide rights to the Roubaix trademark — it’s had a Fuji Roubaix road bike model in its lineup since 1992 — and has licensed it to Specialized since 2003. ASI’s Pat Cunnane said the company has no problem with retailer Dan Richter using the name on his store, Cafe Roubaix.

“We have reached out to Mr. Richter to inform him that he can continue to use the name, and we will need to license his use, which we imagine can be done easily,” Cunnane said.

…

“We are in the process of notifying Specialized that they did not have the authority, as part of our license agreement, to stop Daniel Richter … from using the Roubaix name,” Cunnane said in an email to BRAIN. “While ASI does have the authority to object to Mr. Richter’s use of the name and while we at ASI understand the importance of protecting our bicycle model names, we believe that Mr. Richter did not intend for consumers to confuse his brick-and-mortar establishment or his wheel line with our Roubaix road bike. And we believe consumers are capable of distinguishing his bike shop and wheel line from our established bikes.”

According to the Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Specialized registered the Roubaix name in 2007 for use on “Bicycles, bicycle frames, and bicycle components, namely bicycle handlebars, bicycle front fork, and bicycle tires.”

But Cunnane said that registration was “inappropriate.”

“Like many trademark owners, ASI does not register its trademarks in every country and never tried to register the mark in Canada. ASI only recently learned of Specialized’s registration of the Roubaix trademark in Canada and ASI’s position is that Specialized’s registration of the mark in Canada was inappropriate under the terms of their license agreement. ASI has used the mark in Canada for well over 10 years, giving it first-use trademark rights in Canada.”

In a phone call, Cunnane noted that ASI has been able to reach amicable agreements with several other brands over trademarks. For example, ASI owns the U.S. rights to the name Gran Fondo for use on bicycles, while BMC owns the rights in Europe. The two brands have a co-existance agreement to share the name in both markets.

In this case, it appears not only is Dan Richter's Cafe Roubaix safe from the tyranny of Specialized's lawyers, but it seems that Specialized may have poked a much larger beast than they truly intended. They have essentiall given notice to ASI that they violated the terms of their licensing agreement, and it remains to be seen what the consequences of that may be.

So, while I don't often encourage people to avoid a product or company, I feel safe in my recommendation to my readers to avoid Specialized and their products in the future. If this kind of behavior is contrary to your own moral or ethical principles, vote with your dollars and give them to someone, anyone, else.