The Stages Power Meter burst onto the scene in 2013 with the promise of an affordable power meter option attached to the crank arm. How does it compare? Is it as good as it claims to be? Compared to similar offerings of the time the Stages meter was a novel, if not brilliant idea. It cut the cost in half by placing the measurement device on the left crank arm only. It was easily transferable between bikes and easy to remove and replace if it needed service. The super light weight of only 11 grams also made for an attractive marketing point. So did the user replaceable, easy to source coin cell battery.

Yet not everyone was on board.

From the get-go, many complained about the left sided only power measurement. It was claimed to be prone to inaccuracies due to the “doubling of the left leg” power calculation. Many claimed the accelerometer principle wouldn't provide sufficiently accurate cadence to properly report power.

Here we are more than two years later and Stages power meters can be found on every manner of bikes from weekend warrior up through Tour de France winners.

I've got about 2 years on Stages power meters now. How does it stack up against other power measuring devices I've used like Quarq and Powertap? You can read my thoughts on the Stages power meter after the jump:

Stages Power Meter Features:

Stages Power Meter Features:

Stages is pretty well known by now. In case you're not familiar, I'll give a quick rundown of some of the features of the unit so you'll have an idea of what you're getting into.

First off, let's address the crank arms. Up until very recently, only aluminum crank arms could have a Stages power meter bonded to them. Recently, Stages began production of carbon crank offerings under their own brand name to be retrofitted to a number of different cranksets. The early logic was that aluminum had repeatable and predictable strain characteristics. That's the reason the power meter needed an aluminum arm to ensure repeatability and accuracy. How they got around this, I don't know (I'm not an engineer). So far the test data that's been published looks good.

The Stages power meter unit itself is a small 65 x 30 x 10mm pod that's bonded to the back of the crank arm. It is unobtrusive and lightweight at around 12 grams. The pod manages to tuck in nicely next to the chainstay of most bikes with plenty of clearance. Make sure you check for compatibility first, especially if you have an under-the-chainstay mounted brake like on the Trek Madone 7 or Scott Solace. Some of these frames have clearance issues precluding the use of a Stages power meter.

Accelerometers, BTLE and ANT+

On the more technical side, cadence is handled by an array of accelerometers which measure pedal revolutions. This eliminates the need for zip ties, magnets or any other external parts to measure your pedal velocity. Now, some claim that an accelerometer is a poor substitute for a magnet. That may well be true in applications like track racing. But for everyday use on the road or on a trail, the Stages power meter will fare just fine with its accelerometer-based cadence measurement.

Following the current trends towards integrating with everything, the Stages power meter is ANT+ and BTLE (BlueTooth Low Energy) compliant. This means you can use anything from a Garmin head unit to a smart phone to record your data. And speaking of Bluetooth connectivity, Stages provides a free app to upgrade firmware on their units, which “future-proofs” them, so to speak.

Auto zero and temperature compensation

Other nice features include a running “auto-zero” function which you access by backpedaling 4 times while coasting and automatic temperature compensation. Early Stages power meter units did have occasional issues with power drift when temperatures changed. Firmware updates have resolved these issues for a while now. Finally, the simplicity of a user replaceable CR2032 battery was a novelty at the time. Early Quarq units used a much harder to find CR2450 battery, and SRM required the unit to be sent in for service. Now the CR2032 coin cell is the de-facto standard for power meters.

On the negative side, battery door issues have been well documented among early Stages power meters. Recent updates to the door material ensures the small tabs that secure the battery door on and maintain a waterproof environment do not break off. This is truly the case, with the new, replacement battery doors on my units lasting thousands of miles.

How well does it work?

Now that the technical information is out of the way, what do I think of the Stages power meter? To put it simply, I love it for the simplicity and ease of use. My units have been rock solid through all kinds of weather, from sunny, dusty and rough to rain, dirt and snow. Yes, I experienced the battery door issue, but Stages customer support is fantastic. I had replacement battery doors (yes, plural) in hand within a couple days.

As for the argument that left sided power only is a huge issue, I have to say that practically, it doesn't matter. If you're using your Stages power meter as a training tool to improve your training outcomes, you'll not miss the two-sided power. If you're going to obsess over the data and nitpick over accuracy then this isn't the unit may not be for you. Remember, the MOST IMPORTANT ASPECT of a power measuring device is repeatability and reliability of the measurement. In all practical reality, the +/- 2% accuracy is not a deal breaker.

How accurate is it?

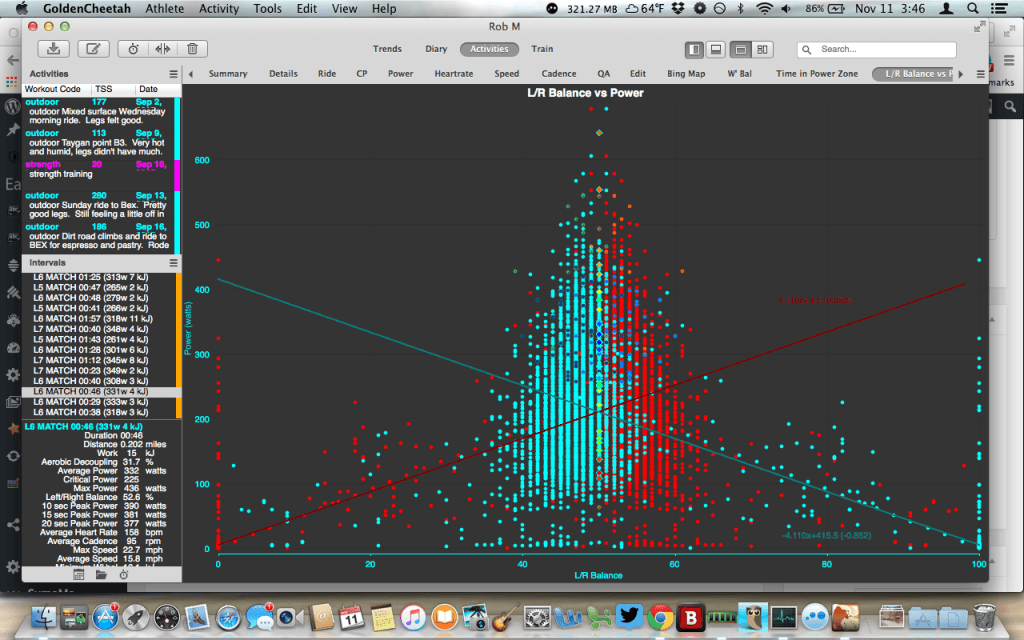

For example, here are a couple of graphs from my training. The first image is taken from an interval performed on my SRAM Red Quarq. First, look at the bottom left for the interval details. You'll see L/R balance of 52.6%/47.4%. +/- 2% is the claimed margin of error of the Quarq Red model this was measured on.

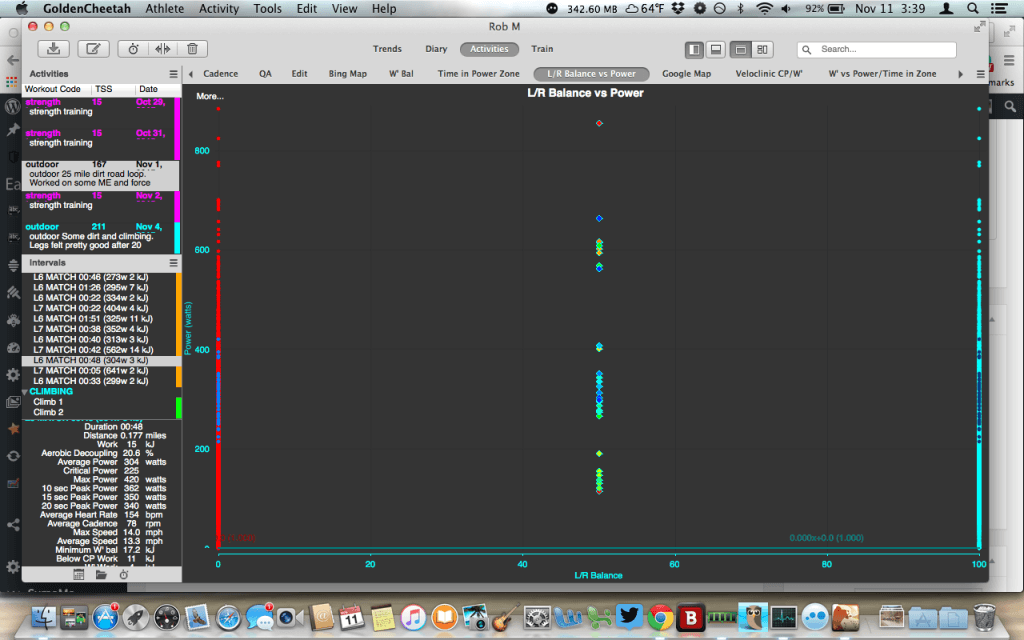

The second graph shows the exact same segment using the Stages power meter to measure the effort. Very similar in duration and power reporting. In fact, the Stages unit (which should be higher due to left leg bias) actually reads slightly lower (but the interval was slightly slower/less intense as well, which correlates.)

When you take into account the margin of error and normalize both sets of data to overlay each other, you'll note that the two are very similar. So similar, in fact, that the difference is negligible.

To confirm that the “left leg only” approach is acceptable, I've repeated FTP tests on consecutive days on the same route with different power meters. The result? They came out within 5 watts of each other. Now, I know this is N=1, but for me, that's perfectly acceptable. Now, if you are HEAVILY biased towards one leg or another (say >5% difference in power from left to right) you may need something with bilateral power measurement to account for this difference.

Finally, you have to consider that at this point in time from a training perspective, we don't have a whole lot of uses for L/R power breakdown. From an injury rehab point of view, I've found some usefulness in working with athletes to iron out mechanical and muscular deficiencies in one leg or the other. Overall, I'm generally finding that most athletes will never find a use for L/R power.

Where does Stages run into problems?

The only other situation I can see the Stages power meter being sub-optimal in would be track racing. Accelerometer based cadence may be too inaccurate and the 1-second reporting may be too delayed to really be meaningful on the track, considering the massive, short power spikes trackies typically deal with. Stages does have a track compatible Dura Ace model, but I've no first-hand experience with it and it seems some others (especially big fast-twitch sprinter types) have had some issues with its accuracy and reporting. I'll reserve judgment until I can get a unit of my own to test, though.

UPDATE 8/2016: I've spent some time on the Dura Ace 7710 Stages power meter for track bikes. Early versions of this power meter firmware had issues with power spikes during sprinting. More recent firmware updates have fixed this issue. I've detailed the installation of the 7710 model in this post. Currently, the 7710 is one of the few reasonably priced track options out there.

The Bottom Line:

The Stages power meter has proven to be a reliable workhorse despite the worst conditions I've been able to throw at it. A Stages arm will run between $529 and $700 depending on the model. This makes it one of the cheapest reliable options on the market today. Backed by top-notch customer service, I'd not hesitate to recommend a Stages power meter to anyone who is even remotely interested in training with power. I've have even gone so far as to recommend it in my “Choosing a Power Meter” podcast.

My recommendation is still to pick up the Stages power meter if you're in the market to start training with power (and you can buy it here.) Now, knowing what to do with all the data is something else entirely. You can check out my Beginners Guide to Power Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and my W' and Effective Workouts podcast for more information there. Of course, you can also subscribe to the Tailwind Coaching Newsletter and get some power training information there as well.