A lot of discussion in cycling revolves around the awesome climbs that separate race winners from also-rans. Amateur cycling is no different with Sunday group rides and Tuesday Night Worlds all being known for the discussion of the “brutal climbs” on the routes. But everyone seems to have a different definition of what constitutes a “brutal climb” these days. So what makes your local hill an actual “climb?”

Read along and see if your regular leg buster is indeed a legitimate climb or if that monster is, by definition, just a bump in the road.

Is It Even A Climb?

Technically we could call any hill a climb, but I have a problem with that. Hills typically conjure up images of rolling dales and mildly bumpy terrain, while talking about climbing conjures images of the Alps or Dolomites. Certainly different riders have different concepts of what constitutes a “climb” and I believe that is where definitions and terminology becomes murky. What may be a climb to a beginner may be a little bump to a seasoned racer. What may be a brutal sufferfest for one club rider may be a thrilling uphill jaunt to another. Therein lies the inherent issue with classifying climbs: it's often down to the rider type and experience.

Climbing Defined by Rider Skill

I propose that we alter the definition of what constitutes a climb, and it should partly stem from the way different riders excel in differing terrain. Short, punchy hills (I hesitate to call them climbs) lend themselves to being tackled by almost every kind of rider in the peloton, particularly “roleurs” who put out a lot of power and can deal with inclines, but fade on longer, sustained or steep pitches. They typically can produce large amounts of power, but they lack the featherlight weight (and subsequent power to weight ratio) to consider them a climber. Looking at the definition from Wikipedia:

The rouleur is a consistent all rounder who can ride well over most types of course. A rouleur will often work as a domestique in support of their team leader, a sprinter or a climber on their team. The best chance for a rouleur to win a stage is by breaking away from the main bunch during the race to win from a small group of riders that does not contain the sprint specialists. The breakaway is most likely to succeed in the undulating transition stages of multi-stage road races, that are neither mountainous nor flat. Examples of such racers include Jens Voigt.

Contrast that with the Wiki definition of a climber:

A climbing specialist is a road bicycle racer who can ride especially well on highly inclined roads, such as those found among hills or mountains. Real free porn movies https://exporntoons.net online porn USA, UK, AU, Europe.

The perfect examples of climbers are riders like Alberto Contador or (as you can see in the Giro) Stefano Pirazzi and Dominico Pozzovivo. These riders put out significant sustained power which, along with their feather weight status, gives them a very high sustainable power to weight ratio (supposedly around 5.9-6.3 watts/kilogram if research and current trends are to be believed.) Additionally, the average climber's skill set includes the ability to attack or cover attacks; they can “go into the red” repeatedly in order to open up or close gaps on their rivals on climbs, and they can typically repeat this effort several times. The roleur may have one or two good, strong accelerations in them before they're relegated to the bunch again.

The perfect examples of climbers are riders like Alberto Contador or (as you can see in the Giro) Stefano Pirazzi and Dominico Pozzovivo. These riders put out significant sustained power which, along with their feather weight status, gives them a very high sustainable power to weight ratio (supposedly around 5.9-6.3 watts/kilogram if research and current trends are to be believed.) Additionally, the average climber's skill set includes the ability to attack or cover attacks; they can “go into the red” repeatedly in order to open up or close gaps on their rivals on climbs, and they can typically repeat this effort several times. The roleur may have one or two good, strong accelerations in them before they're relegated to the bunch again.

But what does all this have to do with determining what is a climb? Good question.

I propose that anything that is easily tackled by a roleur would not be considered a true “climb” while the terrain favored by the true climbers would be truly considered a “climb.” I believe this to be the best way for amateurs and club riders to look at their rides and their terrain. If you're a roleur type of rider who excels at time trials and punchy short pitches, anything that puts you to significant bother for more than three or four minutes would be considered a climb. Those skinny little “mountain goats” that disappear every time the road tilts uphill for three or four minutes are basically in their favorite terrain: a true climb. However, if you want to look at it by the numbers, we can do that too.

Climbing Defined by the Numbers

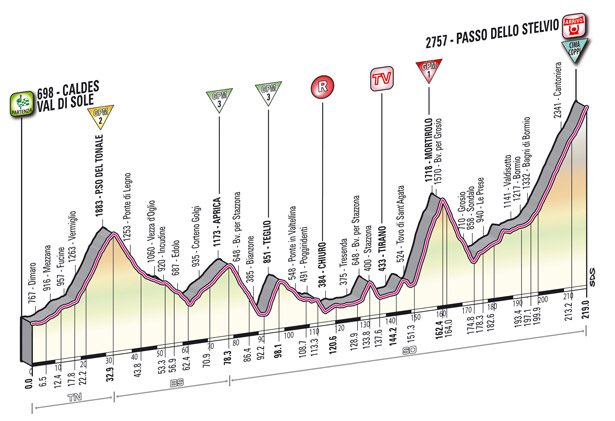

If you want to determine the status of climbs by the numbers, we can look at the classification system used in most professional races. That would mean climbs are classified as 4, 3, 2, 1 (and Hors Categorie or “HC” in the Tour de France.) This determination is made by a combination of length in kilometers and average gradient, with position of the climb in the route and degree of road surface being lesser determinants. See below:

- Category 4 – the lowest category, climbs of 200-500 feet (70-150m). Length is usually less that 2 miles (3km)

- Category 3 – climbs of 500-1600 feet (150-500m). Between 2 and 3 miles (3km and 4.5km) in length.

- Category 2 – climbs of 1600-2700 feet (500-800m). Between 3 and 6 miles (4.5km and 10km) in length.

- Category 1 – climbs of 2700-5000 feet (800-1500m). Between 6 and 12 miles (10km and 20km) in length

- Hors (literally ‘out’ or ‘above’) Category (HC) – the hardest, climbs of 5000+ feet (1500m+). Usually more than 12 miles (20km) in length

As for gradients, typically to classify a climb, the average gradient has to be above 4%. Hors Category (HC) climbs generally average >10% or have an extreme length at a slightly lesser grade.

Strava does a decent job of categorizing climbs by these general guidelines. MapMyRide is less precise: they have climbs down to Cat 5 climbs but they don't seem to follow the rules as precisely.

So what do you think? Does your local hill make the cut, or are you making mountains out of molehills?