Many training plans allude to “high intensity interval training” in their descriptions. The big question is always “what is interval training and how do I know it'll work for me?”

Sometimes, interval training is well balanced and effective. More often than not, though, it is overly difficult and non-specific. You see, designing an interval training program is an art as much as a science. You have to consider the ultimate physiological goal and figure out how to best get there. What durations work the best? What intensities work the best? How many repetitions are optimal?

These questions are all part of the keys to effective interval training. Click through the jump and I'll break down the 3 keys to building your own interval program. At the end, I'll even give you some tips that I use to build interval programs for my athletes so you can build your own interval training programs.

What is interval training and what makes it successful?

What is interval training and what makes it successful?

Interval training is simply the process of performing a set amount of work, usually fairly high intensity, then resting before doing it again. And again, and again, and again. Interval training has long been the mainstay of cycling training plans, and for good reason. By adding interval training to your program, you add intensity and fatigue resistance at a number of different physiological levels.

However, interval training isn't just as simple as “go hard, then rest.” There's a lot of nuance and science behind the kind of interval training that will yield the gains you need to succeed in your goals. It's also a pretty specific balancing act to combine your endurance training and your interval training.

If you want to build your own interval training program, there are a few things to keep in mind. You'll need intensity, specificity, and recovery (in order to get the repeatability you need) in correct balance to be able to execute an interval workout. Let's look at each one of those requirements individually:

High Intensity

Interval work is all about intensity. Yeah, it sounds contrived, but the whole point of performing interval work is to get a significant amount of intensity that you wouldn't otherwise be able to. For example, you simply can't work above your functional threshold power for more than ten minutes without burning out. Your body just can't do it. But you can do interval work that will net you a lot more time above threshold.

Interval work is a trick to help your body handle more training stress. In this case, training doesn't need to be in huge blocks of work, but the repetition of high intensity adds up over time. This is the basic point of doing repeated interval work, but what are some of the nuts and bolts of the whole thing?

Let's dig a little deeper. As you ask your body to work above threshold, you burn up substrates like carbohydrates and creatine phosphate (depending on intensity) to power your muscles. Compared to aerobic metabolism, this anaerobic power production is very limited in its scope. Once you burn up all the substrate, you're done. Your body can't continue at that intensity and has to back down. So, in theory, you're limited in how long you can work at that intensity.

What interval work allows you to do is to work at intensity to stimulate physiological changes, then recover and do it again. That recovery is the key to successful cycling interval training, which we'll see later. But suffice to say, allowing for recovery will increase the total amount of time you spend above your threshold. Instead of ten minutes, you might be able to get 40 minutes of supra-threshold work in a session. That's a big difference.

The big thing you need to note is that you have to have the intensity if you want effective intervals. Lack of intensity will simply not give you the correct adaptations. The reason you're able to hit such high intensities is the availability of substrates and the capacity for high intensity work.

So, intensity needs to be there. But it can't be just intensity, you need a few other things as well.

High Degrees of Specificity

High Degrees of Specificity

Intensity is all well and good, but you also need some amount of specificity in your cycling interval training if you're looking for specific training adaptations. For example, there's a huge difference between the energy system you train at a 1-minute intensity and a 5-minute intensity. In fact, they're so different that you'll be missing the mark entirely.

When you're trying to elicit specific physiological adaptations, you need to ensure you're stressing those physiological systems. If you're not training hard enough, you won't create stress in your high intensity systems. If you train too hard, you'll only get some “spillover” adaptation into the zones you want to train.

Spillover adaptation is a phenomenon by which very high intensity training also creates lower intensity aerobic adaptations. So if this is the case, shouldn't we train as hard as we can each time? Well, no, because we need to combine intensity and volume together for the biggest bang for our buck. That's why we choose to focus on specificity instead of just going all out each time.

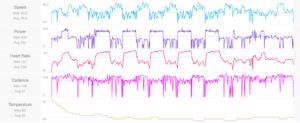

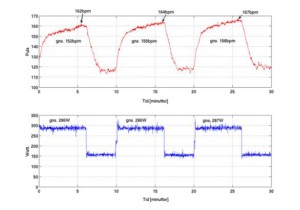

For these reasons, a power meter will be your best option for measuring high intensity efforts. Heart rate simply doesn't have the specificity to handle supra-threshold efforts. While power is (in theory) infinitely measurable, heart rate is very limited. As you reach functional threshold power, heart rate is a good training metric. However, when you start getting towards VO2 max, heart rate maxes out while power can continue one.

So heart rate is capped out. Combine that with a significant lag in heart rate response when you increase intensity and your interval could be over before your heart rate catches up. For the sake of specificity, use a power meter to drill down into your numbers and pick the right intensity to create the proper training adaptations. Sure, you can use RPE in a pinch. There's even some evidence that it's just as good as a power meter. But there's definitely a benefit in having hard data to reference when you evaluate your training and racing.

Along with intensity and specificity, you need one other thing to ensure a quality cycling interval training session: recovery.

The right amount of recovery

One of the biggest tenents of interval training is the amount of recovery involved in between efforts. The whole point of doing intervals is to train at a high intensity for a specific amount of time and then recover for a set amount of time. The recovery is important because it's the time your body recharges and prepares for another effort. As mentioned before, without recovery time, you simply don't have the energy substrate necessary to execute further intervals. Without the correct amount of recovery, your later intervals will suffer due to fatigue. Каталог на тягови батерии. Акумулатори за мотокари купувайте ниско. But recovery is more than just rest, it's part of your overall plan to create physiological adaptations.

In some cases, you can manipulate the recovery periods to achieve specific goals. For example, if you're a crit racer and you're looking to build repeatability and the ability to attack, recover and attack again, you'll need to focus on recovery more than interval intensity. The shorter recovery involved in intervals like this simulate a real-world situation. It forces your body to tap into energy reserves and stimulates your body to store more glycogen in preparation for similar efforts in the future. It also creates overall adaptations in the form of increased anaerobic work capacity (or W' as I detailed in this post.)

Building a cycling interval training program

Building a cycling interval training program

In my previous posts on high intensity interval training, I went over the physiology of high intensity training in detail. I also gave some tips on how to build an interval training program. If you're just looking to add some interval work to your regular riding, you can check out my VO2 max workouts, my 1-hour workouts or my Zwift workouts.

If you're looking to do the programming yourself, here's a couple things to keep in mind:

- Initially, work intervals and rest intervals should be of equal length to ensure you can execute the interval. As you get stronger, you can reduce the rest interval by up to half.

- Start with your weakest interval duration (which you can find by testing or reading your mean maximal power curve) and expand both directions from there. For example, if you're weak around 5-minute durations (VO2 level effort) start with 5-minute intervals and expand to 3 minute and 8-minute intervals as well.

- Begin with 3 reps of each interval and expand from there. For example, a set may be 3×3 minutes of VO2 work at 120% of FTP with 3 minutes rest between. After you can complete the 3 intervals, add another. Once you can complete 4, add another, etc. Keep that up until you hit about 30 minutes per interval session of intensity.

- Don't try to be a hero and do back to back to back interval days. While it's true you can recover better from interval work because the volume is lower, you'll eventually burn out doing this. I'd recommend no more than 2 days of interval work back to back. If you really want to do 3 or 4 days of interval work in a week, mix in rest days or endurance days in between.

With all the tools to start your interval training, what are you waiting for? Get out there and build some big fitness in preparation for your early season goals!

If you've got questions or want me to help you build your program, don't hesitate to contact me and I'll get you squared away.